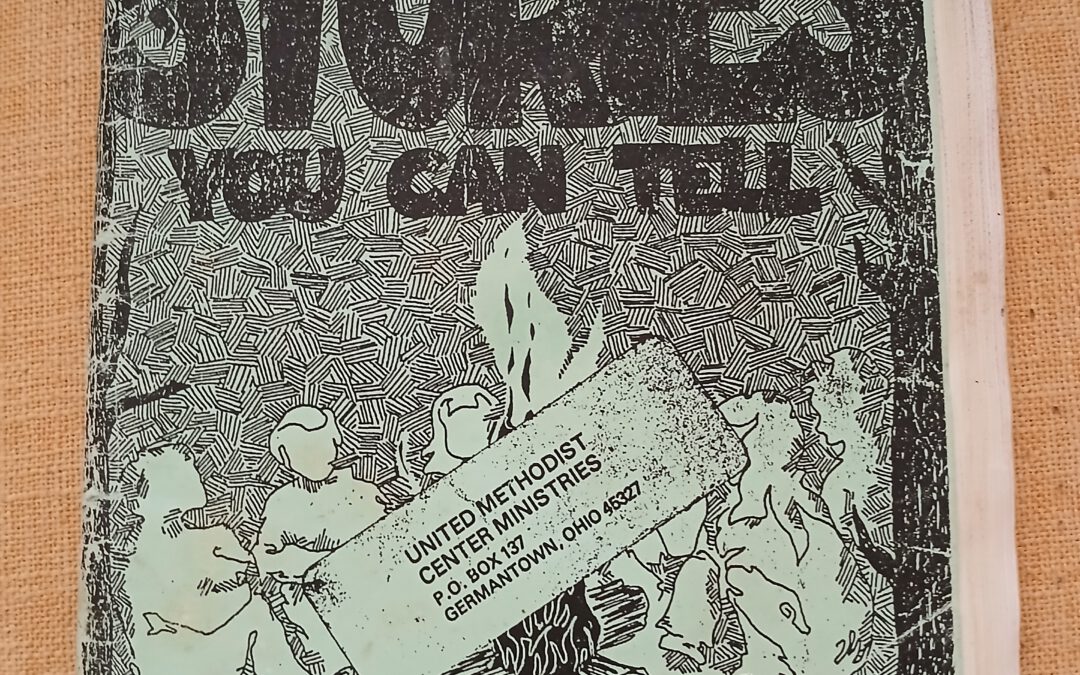

When I was a camp counselor during my college years, I used to have this little story book called Stories You Can Tell–old, weathered, beat-up, overly re-copied–that rode around in my backpack, summer after summer. Our beloved camp director, Christina, a beautiful hippy with a long, black braid that fell down her back, issued us a copy of the little zine at the top of each summer during staff training, along with our fanny packs stuffed full of first aid supplies. I think of this book, and the many, many times I got to tell stories to children at camp as a huge part of my journey toward where I am today.

When I was a camp counselor during my college years, I used to have this little story book called Stories You Can Tell–old, weathered, beat-up, overly re-copied–that rode around in my backpack, summer after summer. Our beloved camp director, Christina, a beautiful hippy with a long, black braid that fell down her back, issued us a copy of the little zine at the top of each summer during staff training, along with our fanny packs stuffed full of first aid supplies. I think of this book, and the many, many times I got to tell stories to children at camp as a huge part of my journey toward where I am today.

Side note: Somewhere along the way during the Atlanta Fringe Festival performance of Teapot earlier this year, I announced that I’m already beginning to work on my next show: Camp, Unrequited Love, & Unrequited Love at Camp. Stay tuned!

There are two stories in Stories You Can Tell I will never forget. The one about “Warm Fuzzies,” which is a sweet allegory about capitalism, how it divorces us from our innate knowledge of how to support and soothe each other & ourselves without the need to buy stuff. The other story I think about even more frequently is “The Island of Seven Kingdoms.” I have tried valiantly for decades now to tell this story in all kinds of places and contexts. Typically a personal storyteller, it may just be my attempts to tell something more like a fairy tale have never worked because it’s not natural to me. I think it’s really the ending I struggle with. I never seem to nail the landing. (I’ve often said that endings are the most underestimated and important part of storytelling.)

In “The Island of Seven Kingdoms,” a young adventurer (I change it from a boy to a girl in my delivery because: feminism) sets out to discover where the natural water source that long ago vanished from their island has gone. The island is divided into separate kingdoms by high walls that radiate out from the center (rather like a Trivial Pursuit piece). Each kingdom hates and fears the next, each carrying deep prejudice and stereotypes–“that kingdom is full of robbers,” “the next one will kill you dead.” The young person sets out to each kingdom, trying to figure out if anyone knows where the water has gone because they are all very poor, having to independently broker with nations in other places to bring in fresh water because they cannot get along, and water is very heavy, very expensive to import.

In the end, our young (s)hero figures out that the water is a spring that runs out in seven rivers. It has been there all along, buried underneath the walls as people’s hate and fear of each other caused them to build higher and higher barriers from each other, eventually sealing off the rivers, forgetting they ever existed.

I really hope one day I can tell that story right and well. It’s got a lot of potential. A salubrious story for our time.

By contrast, there are a lot of stories of scarcity going around right now. When I hear the word, scarcity, it always makes me think of its sister word, scary. Scarcity and scary are like two fists, simultaneously clenching at my stomach and my throat. Makes me not want to turn on my beloved NPR station in the morning. Speaking of, NPR & PBS are under attack. Please consider kicking them some dinero if you can!

Stop me if you’ve heard this, but I do believe there’s great power in the stories we tell. (Story nerd!) They shape and bend the arc of our moral imagination. Please hear that I’m not at all endorsing that we should bury our heads in the sand, ignore the very real suffering that’s happening in the world. Nonetheless, it’s imperative to keep turning our heads toward our own collective abundance and possibility right now, whenever and wherever we can.

Recently, I was working with a new coaching client who had just drawn her life map. We worked from there on which story she wanted to put together from within the map to create an overall plot to then weave into an upcoming speech she’ll be giving to donors at the end of the summer. We talked about the importance of finding the change (as important as a sticking the landing!) and theme of her story. As we explored the possible combinations–this moment could lead to this moment, which highlights this theme–we started geeking out together on the multiverse of possibilities just within the container of 4-5 stories you could tell. It can all become dynamic, like a choose your own adventure book, depending on the need for that story.

Recently, I was working with a new coaching client who had just drawn her life map. We worked from there on which story she wanted to put together from within the map to create an overall plot to then weave into an upcoming speech she’ll be giving to donors at the end of the summer. We talked about the importance of finding the change (as important as a sticking the landing!) and theme of her story. As we explored the possible combinations–this moment could lead to this moment, which highlights this theme–we started geeking out together on the multiverse of possibilities just within the container of 4-5 stories you could tell. It can all become dynamic, like a choose your own adventure book, depending on the need for that story.

In the end, stories are one of our most renewable resources. Try to wall them up, prevent people from hearing them, burn them or ban them. People’s stories–their imaginations–cannot be limited.