Dear Kids,

I was 14. Bored in biology class, I started making lists of the names of my children. Just like the book I’d been reading, Flowers in the Attic, I would have a girl, and then a boy, and then a set of fraternal twins. Their names would be Catherine, Christopher, Cassandra, Charles…

I was about nineteen or twenty, a tempestuous college student prone to equal bouts of depression and frenetic joy. I found myself walking up a familiar flight of stairs at school one day. At the top of the landing was an enormous painted portrait of an old man in a grey suit with white hair. I’d come to stare at it almost every day as I trudged or bounded up the stairs, depending on my mood.

[Kids, you need to understand that this was before the age of smartphones, so people would look at things around them as they walked.]

I always assumed the painting was of a long-passed professor or college administrator. To this day I have no idea who he really was. He just sat there with his smirk, a careless arm propped on a table, acting as hall monitor, day in and day out.

On this one particular day, I looked the old man straight in the eye and had a strange moment of–connection? Epiphany? I felt like I was seeing him as a young boy, and then as a baby. Right then and there, I imagined I was hearing from the child I would one day have. Like the idea of him was planted in my belly long before fertilization would come. I thought I was talking to you.

At 23, I was locked in the existential struggle known as “post-college with an English degree.” Bumping along through life with so many questions and not enough answers, I had about twenty jobs in two years. One of them was part-time nanny to a very young baby. His mom was a journalist who teleworked back in the days before anyone had ever heard of that.

She would pay me to come and take care of her little guy a few days of the week so she could concentrate on work. He and I would sometimes just hang out at the house, but because this mama was a big believer in natural vitamin D, we would also get out with his stroller and walk all over town for a few hours.

As we strolled along, I would fancy that this was my baby, sometimes even let people in shops and restaurants assume that was the case. I was living in a university town. We would walk across campus, as I peered through the windows of academic buildings. Sometimes I imagined I was a grad student or staff or even faculty member there. I spent a lot of time during those days, trapped in a liminal space filled with fantasy and disconnection, feeling like I didn’t belong anywhere. I appeared to be a mother, a student, or a professional, but I was none of those things. I was simply lost.

I was 29. My grandmother was 89. Approaching her 90th birthday, she started making predictions. It was a short list. Every time I saw her, she started handing out predictions and making sweeping declarations as people that age sometimes begin to do.

My sister was pregnant at the time, so my grandmother said she wanted to see her first great grandchild born. She wanted to live to be 90. She wanted to see me become…a stepmother.

A stepmother? I remember the first time she said it. I just sat there and looked at her silently. Where was this coming from? I was 29, had never had a real romantic relationship, yet she’d already given up on my fertility.

Her list morphed over time as she lived past ninety. She said she wanted to see her second great grandchild born. Eventually, she just wanted to see me finish grad school.

Toward the end of her life, she didn’t have a list anymore. She was just really ready to be done with life and all its to-do lists. If you could have seen her in those final years, you would understand.

I was about 30. I had been struggling through my first couple years of grad school. My program was calling on the deepest parts of me. Not just academically, but in a deeply personal way. It kept asking me to figure out who I was, who I wanted to be in the world. To stand up for myself in the face of power and labyrinthine administrative structures, even grown-up bullies. The stress brought on a whole bevy of physical symptoms, including vertigo, blurry vision, and migraines.

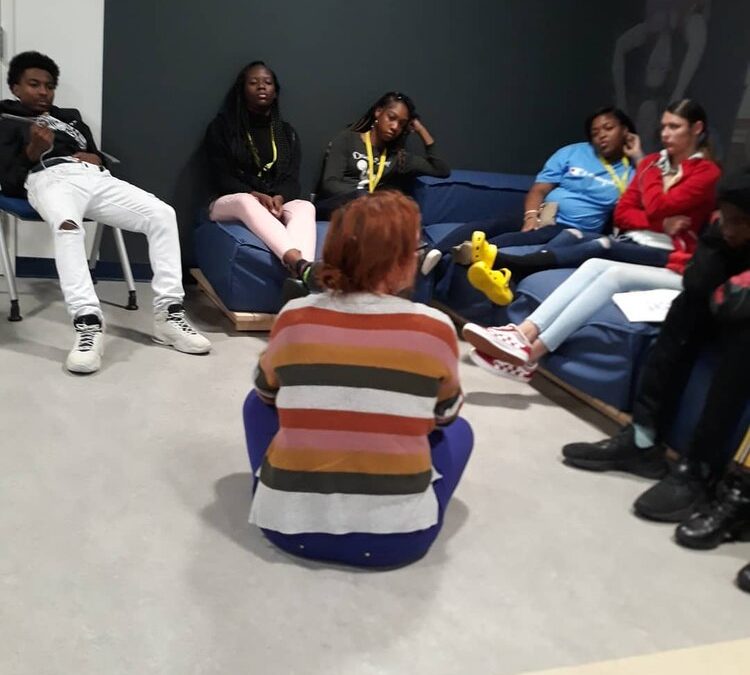

Somewhere in there, I went to Alternate ROOTS’ annual gathering for the first time. (ROOTS is an organization I would eventually work for and devote six years of my life to.) It was mid-afternoon, and we were soaked through with rain in that way that happens in the mountains in summertime. The barometric pressure had brought on yet another migraine. After medication, I was starting to climb out of the dark place with a racing heart and shaky hands. Our business meeting was paused by an art moment–perhaps the best possible thing about ROOTS–a performance led by the luminous Laverne Zabielski, a fabric artist from Kentucky. A young Black woman, then an older white woman, then a middle aged woman in a wheelchair, then another young woman, all paraded through the audience as Laverne read a poem she’d written about womanhood. In the poem, she listed and celebrated various parts of a woman’s life. At some point, she described how we define ourselves in relationship to being or not being a mother. She read words that went something like, “and all the children you did not have but wished you did,” I burst out crying and ran from the room.

I’d like to blame the migraine medication, or the inordinate stress I was under all the time during those years. Somehow, though, that line just zinged me. It opened up a new passageway in my mind. Maybe I would not have children. Maybe I would never get to meet you. Maybe I didn’t even realize I was sad about that. I was 30. I had never even had sex.

I was 34. I’d moved to Atlanta and finally begun to seriously date. The possibility of accidentally conceiving a child was now on the table. I was with a man who was divorced and had children. [This would become an ongoing trend as I’ve found the chances are pretty high when you reach a certain age that the person you’re trying to date has already been married and had children.]

One night we got into a conversation about whether I wanted to have a baby. Thoughts I didn’t even realize were in me started to tumble out of my mouth like when you open the dryer still in motion and all the clothes spill on the floor.

“I feel like I’ve already missed my window,” I said. My beau looked at me, shocked, and asked how I could think that when I was only 34. I mapped out a timeline that involved society’s prescribed formulas for how long it takes to meet someone, date, decide to marry, and then have children. I also wondered aloud if perhaps it would be best if I didn’t hand down some of the genes for physical and mental illness I carry. As I sat there saying all of those ridiculous things, I felt like I was making my own prediction, or maybe just solidifying the one my grandmother had made. I too had already given up on my fertility. Perhaps, I would be a stepmom. Perhaps it was because I didn’t feel worthy to have children of my own. I didn’t feel worthy to call myself your Mom.

I was about to turn 39, in yet another relationship with a divorced dad. This one was different. It felt like this one could have been my lifelong dance partner. Long before we met, he had a vasectomy, which meant at least I knew where we stood with the idea of having children together.

We spiritually pushed and pulled against each other, month after month, trying to decide if we fit. One day, we stood in a doorway. A literal doorway, between his closet and bedroom. I mentioned my approaching birthday. I said to him, “I know that whether we wouldn’t have children together, but if you don’t want me, you should let me go sooner rather than later. If I wind up with someone else who wants children, I only have a couple of years left to do that.”

He looked down.

He couldn’t decide that for me. Our relationship ended just a few months later; we spent three more years dancing in and out of each other’s lives.

Whether consciously or unconsciously, I let the last few years when I could biologically have children go by as I waited for a man I knew was never coming back, and he wouldn’t have children with me even if he did.

Today is Mother’s Day, and I’m 43 now. One of my dearest friends is pregnant as I write to you. Every week, I look forward to walks with her. I sneak sideways peeks at how her body is changing each week. I wonder what it’ll be like to be around to help with this little one after it comes into the world.

Even if I don’t ever land the part of stepmom, I know from experience that aunt is one of the best, if more underrated, jobs on the planet.

Sometimes I put my hand down on the soft, rounded pooch belly that has always been part of my body, no matter how much weight I gain or lose. It makes me wonder if it’s my body expressing the grief of a child that will not grow there.

I say all that by way of apology and explanation to you, my unborn children. I still can’t decide if I made the choice intentionally or unintentionally. I never felt I could do it on my own. I certainly get lost down rabbit holes about climate change, political turmoil, all you would face if I’d brought you into the world. The chaos previous generations would be leaving to you.

Truth be told, I have a far deeper sadness because I have not found my lifelong dance partner than that you are not here…

This is an excerpt from Walks with Grief, a work-in-progress that may take me a million years to write at the rate I’m going.

Sharon,You are fearless. This is so good. Keep going. John

Thanks, John. Appreciate your ongoing support.

That was amazing Shannon. I wish I could just give you a big hug.

Sent from Yahoo Mail for iPhone

Thanks, Paul! Appreciate your support.

What a fantastic post. Life takes us on very different roads that don’t always fit the narrative in our heads.

Thanks, Gail. And that’s for darn sure!